“Whatever It Is, It’s You”

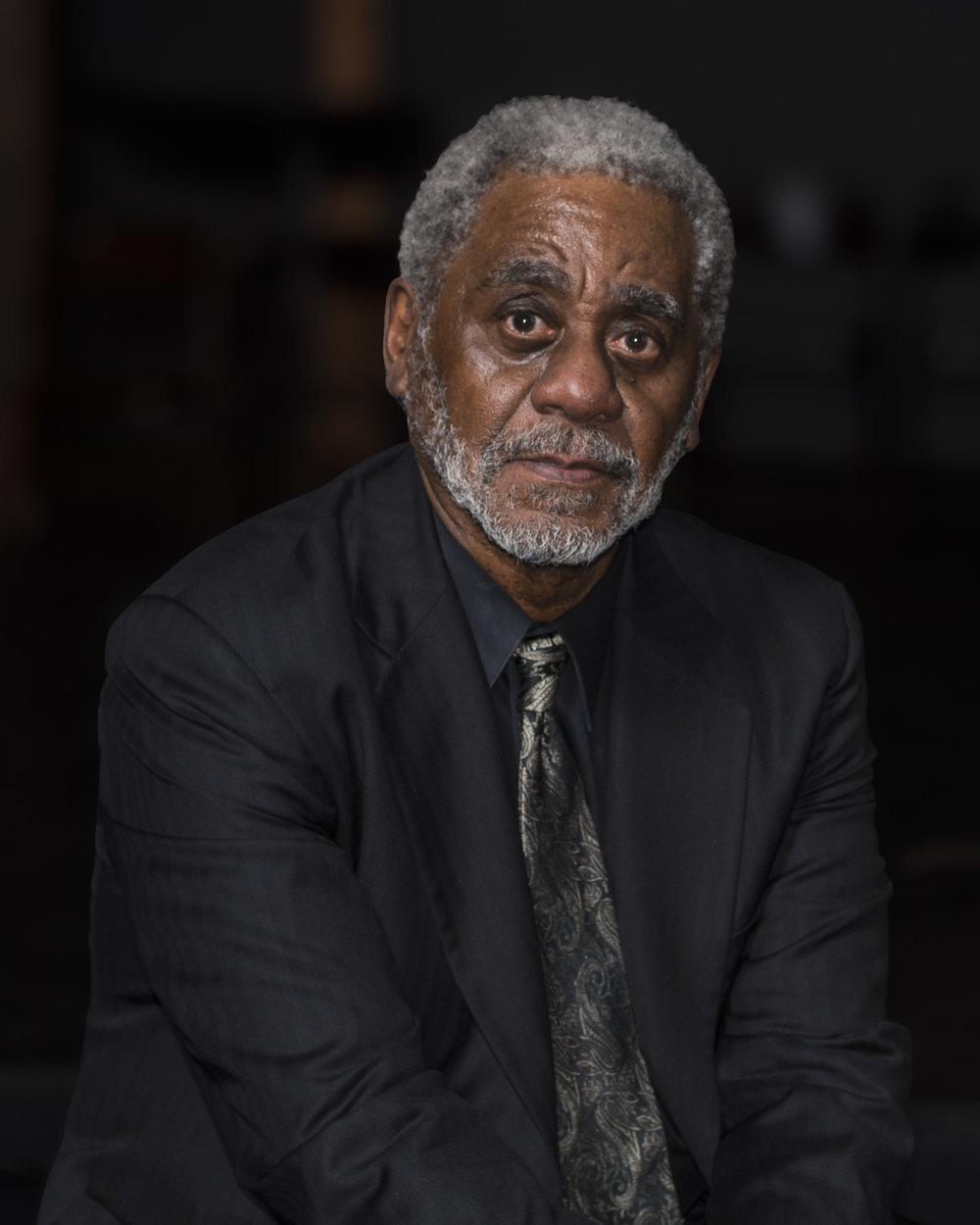

A Conversation with Charles Johnson

Ursula K. Le Guin once said she was fortunate to have discovered the Dao De Jing as a young girl, for she could have it for the rest of her life. While in school, I was fortunate to have found Charles Johnson’s Oxherding Tale and Middle Passage, Buddhist retellings of America’s darkest history that reaffirm life beyond the horror and dehumanization of slavery. I read his The Way of the Writer and Night Hawks when they were first available a few years ago, and now his latest, Grand: A Grandparent’s Wisdom for a Happy Life. These books will accompany me for the rest of my days.

Although it was published in May 2020, I’ve only recently read Grand, partly because it appears to be written for a parent or grandparent, and I’m neither. Separated from my mother at eight when I escaped Vietnam on a refugee boat and having lost both parents by sixteen, I’m far from Johnson’s eight-year-old grandson Emery, who is described as “confident and self-assured . . . growing up in a home of very educated, creative people.” Johnson dedicates this book to Emery.

Once I perused the table of contents and delved into Grand, I prolonged the reading experience as much as possible. Grand made me think, laugh, and cry, filling me to the brim with sadness and happiness all at once; in it I hear my ancestors’ voices and can imagine that my grandparents and my parents would share these perennial truths stitched by their own life stories.

How is it that these words speak to me, an American of Vietnamese descent, nearing the midpoint of her life? How is that I find hope and comfort in them amid our upended world with the pandemic, job losses, children at the border, and rampant racial violence? I read and reread Grand to help me meditate on our troubling time. I reached out to Johnson, whom I have not met, but in whose wisdom I found a safe harbor. Below is my email exchange that took place over a month with the National Book Award-wining novelist whose works are informed by his roles as a philosopher, writing mentor, Buddhist, cartoonist, and martial artist.

Thuy Da Lam

Am I overstating to describe Grand as a book for everyone and no one—to borrow Nietzsche’s Zarathustra’s subtitle? In our current time, how can we find, as you state, “the goodness and beauty that life offers”?

Charles Johnson

Thank you for your rich and moving message today. I’ve read it several times now, with gratitude for your kind words for Grand, and even greater thanks for you letting me know more about your own history, which I think is special. Very special.

My intention was for Grand to be for everyone. My hope was that what it says in those ten short chapters is perennial and universal, touching on matters we all share as human beings. A few days ago, my Chinese colleague at the University of Washington, Shawn Wong, told me he will be teaching a course with Asian students this summer, and that he has Grand on their reading list. I’ve agreed to join his class for a discussion of the book on Zoom. So what you’re saying is true, I think, because those chapters draw on wisdom from all over the world, from the East and the West. No one owns wisdom. Or truth. I’ve always felt, as a philosopher (the word philosophy literally means “the love of wisdom”), that I should embrace wisdom wherever I found it. I feel fortunate that I’ve found it in many places. I’m always open to receiving more . . . and with the profound gratitude I feel for your email today.

Thuy

When reading Grand, do you recommend the reader read the chapters chronologically?

Charles

I believe that the first chapter, “Know Thyself,” is foundational for all the chapters containing advice for my grandson. It would be helpful to a reader to experience that chapter first and the chapter titled, “To Love is to Live” last. The others can be read out of order.

Thuy

Your four words “No one owns wisdom” is heartening and liberating for one who’s seeking a home in the world. Do you think that by drawing “on wisdom from all over the world, from the East and the West,” we’re not only examining our lives through wider, multifaceted lenses, seeing ourselves from different angles and at a deeper level, but also making visible the web of our interconnectedness? By recognizing our interdependence, will we then be able to act with greater empathy toward one another and cultivate a sense of universal responsibility?

Charles

I couldn’t agree more with what you say. As you see in Grand, I would counsel my grandson to understand the line, “Whatever it is, it’s you.” In other words, I want him to see that he is meaningfully connected to every person, place or thing he encounters in life, if he will just look closely enough at it.

Thuy

Early in life, I realized that who I am is due to what and whom I love. My outlook was more stoic than joyous until I read your words: “And in my life I’ve loved so many things. The challenge was also how to bring them all together, unified in a single life.” What obstacles might prevent us from achieving our destiny, driven by our deeds, will, and desire, as captured poetically by the lines from the Upanishads you end the first chapter on “Know Thyself”?

Charles

From my early life forward, it has always been a challenge for me to bring together all the things in my life that I love, partly because there are so many things that I love—drawing, writing, family, philosophy, martial arts, Sanskrit study, a passion for the sciences (and science fiction), chess, comic art, and Buddhism. But I think what I’ve realized in 72 years is that all these things are connected and overlap, if one approaches them creatively, as I’ve tried to do. Perhaps I’m a dabbler in many things, and a master of none. But maybe—just maybe—after so many decades devoted to those things, some mastery has been achieved in a couple of them. For me that will be enough. And I deeply admire and appreciate those people who have achieved mastery in a single field I haven’t been able to devote myself to full time.

Thuy

I feel calm when I read the title of your second chapter, “Life Is Not Personal, Permanent, or Perfect,” an observation from Ruth King’s Mindful of Race: Transforming Racism from the Inside Out, a book that you want Emery to trust. I will continue to practice “egoless listening” as you wish Emery to do when others judge us based on our appearance. I will remind myself that there’s no I, no essence, and that Thuy is not a fixed, static entity. But what about when we are faced with physical harm, when our bodies are treated as nouns, and the perpetrator commits Whitehead’s Fallacy of Misplaced Concreteness? What should we do as the target of physical violence and as witnesses?

Charles

I think, as I said early in Grand, that we so often will be seen by others through the lens of their own limitations. Right now in this country there are too many horrific attacks on Asian Americans that sicken me. Each and every one of them. I value and revere my Asian teachers, like Choy Li Fut kung fu grandmaster Doc Fai Wong in San Francisco. Like my friend, the late spiritual teacher Sri Chinmoy. Their attackers know nothing of the richness of their personal lives, their history, and contributions to this society. As a martial artist, I believe those elderly Asian American who have been targeted by deluded, cowardly bullies should have a younger person trained in self-defense to accompany them whenever they go on walks or to do necessary things like shopping, at least in the short term until the waves of irrational hatred and anger unleashed in this country subside. And we all—especially if we are writers and artists—have the duty to bear witness to any crime against humanity.

Thuy

You mentioned that by approaching your many passions creatively, you’re able to see how they’re connected and overlap. What is it about art that allows us to work beyond the established divisions of categories, disciplines, fields? Is it also through art that we can free ourselves from what Einstein calls the “prison” of our experiences, which are limited by time and space? How can an individual transcend temporal, spatial, and spiritual boundaries and live life with compassion, creativity, and agency?

Charles

I fear that many artists and writers I know are in the prison of limited perception that Einstein spoke about. In chapter 30 of my recent book on writing craft, The Way of the Writer: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Storytelling, I used an epigraph from the great literary scholar Northrop Frye that I’ve always liked: “It’s not surprising if writers are often rather silly people, not always what we think of as intellectuals, and certainly not always freer of silliness or perversity than anyone else.”

In order for a person to live life with compassion, creativity, and agency, I think it’s helpful, and maybe even crucial that he or she has a spiritual practice that can center and ground them throughout their day. By itself, it’s difficult for art to do that. Always and forever—in spiritual practices and in art—one must put aside the ego in order to fully experience compassion for others (real or fictional), creativity, and personal agency. That at least has been my experience.

Thuy

Evoking King’s sermon “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” you advise Emery and all of us to “never ignore the spiritual register in our lives.” You quote King, “we were made for God, and we will be restless until we find rest in him.” What does “the quest for the divine” mean for people of different faiths? Chapter 4 of Grand ends tersely and provocatively with two one-sentence paragraphs. Is the search for the divine a personal journey that each of us must go through? That we should seek to cultivate a spiritual practice within the context of our everyday lives?

Charles

People with different spiritual practices must answer the question about the “quest for the divine” within the context of their particular religion. I can’t speak for each one, but I think a common thread that runs through the major religions with which I am familiar is the unity of life. Without a spiritual practice, our lives are more impoverished and not as rich as they can be if each and every day what we do is informed by the wisdom of those who came before us in whatever spiritual tradition we embrace.

Thuy

I want to wholeheartedly accept the title of Chapter 5: “Suffering Is Voluntary or Optional.” In his personal account, Brian McDonald shared that through empathy, he was able to understand that it was the system that killed his brother, not the man who pulled the trigger. McDonald, you write, “understands that pain is an inevitable part of life, but suffering is voluntary or optional.” How can a person cultivate this mindset early in life?

Charles

The answer, I believe, is quite simple. We must teach our children and grandchildren at a very early age that all life is precious, theirs and the lives of others. And each is different and unique, like no life that has ever been before or will be again. Each life has its integrity and value, regardless of the circumstances surround it.

Thuy

How can I say “suffering is voluntary or optional” to someone without feeling guilty of my seemingly fortunate circumstance and the other’s inescapable situation?

Charles

In Grand, I try to provide the best guidance I can to my grandson and any readers of that book. But I think each individual reader will have to interpret and fashion his or her application of the ten items of advice to fit their own life, their own circumstances, and their own history. This is something I know I have to do in my own daily Buddhist practice. Yet despite our differences, I do believe there are common threads that run through the ten items of advice. One is very old wisdom: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Another thread is humility (Trying not to see others in terms of our ideas about them but instead giving up our assumptions, presuppositions and prejudices in order to experience and appreciate each person we come into contact with.) And a third is empathy and compassion for others. I’m pretty sure one can’t go wrong if we approach others in the social world in this way.

Thuy

Chapter 6: “Experience Something Beautiful Every Day” resonates with me in many ways as a reader, writer, daughter, and sister. The short story “Kubota Garden: A Zen Sketch” comforts, inspires, and guides, offering possible signposts for me to proceed with asking and answering my own questions. Near the end of the story, you describe “the water flowing freely, capable of assuming the shape of anything. Joshua felt he could do that now, for in just this past hour the Garden had nourished his spirit, showing him the littleness of what people called ‘race’ in the vastness of Being.” The above passage (along with many others) takes my breath away. Can you advise how a teacher can guide students to remain open to “the vastness of Being”? Can you suggest a writing task that helps students to understand “race” and “the vastness of Being”?

Charles

Yes, there is a very simple exercise anyone can do. Ask students what is the genesis of any object before them. It could be a cigar. A bath towel. How did it come to be? What is the history of that object? How did it arrive in your hands? Careful analysis will reveal that nothing made by people comes into being ex nihilo, or all by itself. Its history probably involves many peoples and cultures. I use two examples to illustrate this, one from Martin Luther King Jr., the other from Guy Murchie when he reveals how every book we hold is indebted to the Chinese who invented paper, Indians who invented ink, Germans who gave us type and who used Roman symbols they took from the Greeks who borrowed their letter concepts from Phoenicians who adapted them from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Thuy

Can you share a bit on how you used your handout on the “45 Logical Fallacies” in your creative writing classes?

Charles

I asked my students to think about them because, as philosopher Richard Hayes once said, about 99% of what people say involves a logical fallacy of some kind. I didn’t want such fallacies in thinking and argument to arise when we discussed the work of students in my classes.

Thuy

Have you read a literary work or works that are driven by one or more logical fallacies but that move you emotionally? Why is this?

Charles

Because people commit logical fallacies all the time, characters in fiction do so as well, and often act on them with tragic results.

Thuy

Does tending to logical fallacies curb one’s creativity and imagination, which in part are born from our (arguably illogical?) emotions—passion, desire, suffering, fear, anger, and so on?

Charles

No, I don’t think our creativity and imagination are curbed if we in our personal lives are logical, mindful, and in control of our emotions. In my short story “The Weave,” a character is upset by being fired and steals from her employer out of, I guess one would say, passion, the feeling of being hurt, etc. But I cannot steal. The injunction against that is one of the ten vows (Precepts) that I took in 2007 in the Soto Zen tradition. Another example might be Greek tragedy, something like Oedipus Rex. My mentor John Gardner once told me that after the performance of that play, the ancient Athenians would join hands to reaffirm their sense of community and their desire not to be like Oedipus. Whether that’s truth, I can’t say, but the idea behind this statement—the difference between life and art—seems sound to me.

Thuy

“Everything he does in his school or away from it,” you advise Emery, “should involve spirit first, technique second. (I dare-say that principle also applies to writing and drawing and any of the arts.)” Can you give us a peek into your process in which you apply this principle of “spirit first, technique second” in the writing of one of your short stories or novels?

Charles

In the Way of the Writer: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Storytelling, in the chapter titled, "On Craft and Revision" (p.77), I offer readers a description of how I recommend moving from a first draft to a third draft in one’s writing. I also remind readers that my ratio of throwaway to keep pages can often be as high as twenty to one, and that is just a natural part of the process of revision.

Thuy

Is there an author whose body of literary works that you admire and that suggests the writer has cultivated what you call “the Beginner’s Mind of Zen, a mind and spirit always fresh and open, not fixed or frozen, always flowing like water”?

Charles

As an example, I’d suggest any of the great Zen poets like Basho.

Thuy

In Chapter 9: “Never Stop Learning,” you recount, “When I received a MacArthur Fellowship [in 1998], my present to myself, at age fifty, was the systematic and sustained study of Sanskrit, a language that had fascinated me since the late 1960s.” You conclude the chapter with a powerful avowal: “My grandson Emery will see that Sanskrit is my most serious intellectual and spiritual hobby, a language I will study until the last day of my life.” Your relationship with Sanskrit—its central roles in your aim of being a lifelong learner and in unifying mind, body, and spirit—is inspirational. How can a person find a hobby that he or she wants to engage in every day, even on the last day of life? What criteria should the person keep in mind when choosing this activity?

Charles

I would say that each person has to find that hobby themselves. Another of my hobbies since my teens is chess, and a few years ago I received a U.S. patent for a different, non-war-like way of playing the game that came to me when I was writing my novel Dreamer about Martin Luther King Jr. and the strategies of the civil rights movement. I consider chess to be the greatest board game ever invented, and the mental activities I enjoy—strategy, thinking ahead for several moves, focus and close attention to something—are all there in the process of playing the game.

Thuy

I think all languages have the ability to gain the love of a learner. How can the learner cultivate and sustain a lifelong love for studying a language?

Charles

As I said in Grand, foreign language study was never my forte, though since my teens I studied Spanish in high school and as an undergraduate, then French to earn my master’s degree in philosophy (a reading-only course). Sanskrit differs from those two languages for me because my spiritual practice is Buddhist and so much of the literature—sutras, for example—is in Sanskrit or Pali. In other words, I can be passionate about Sanskrit because I’m passionate about the Buddha Dharma.

Thuy

What does a life of fearlessness awakened by love look like?

Charles

Put simply, it feels wonderful to be with someone who appreciates and loves you just as you are, as you love that person. There is a feeling of wholeness and inner peace as a human being when you are together, helping one another in mind, body, and spirit. For me this kind of love brings a profound feeling of gratitude, humility, and thanksgiving. And such a love between two people is so abundant it spills over to their loving and feeling compassion for others. It also gives me the feeling that there is no challenge in this world that I am not up to confronting, because I know I am loved and have been given the opportunity to fully love another whose gift of love awakened me to myself. I know that such an experience of love is rare.

Thuy Da Lam is the author of the debut novel, Fire Summer. She received her BA in creative writing from Hamilton College and PhD in English from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Like Charles Johnson, she fell in love with philosophy in college and has pursued the love of wisdom since. Outside of teaching composition as an adjunct lecturer at Kapiʻolani Community College, she finds deep satisfaction caring for a patch of land beneath the Koʻolau Range.