What Color Is Your Scapegoat?

With her short story collection Light Skin Gone to Waste, the 2021 Flannery O’Connor Award-winner, playwright, novelist, essayist and provocateur of identity asks tough questions about her family—and, here, discusses the built-in expectations that, in her view, get in the way of creative life.

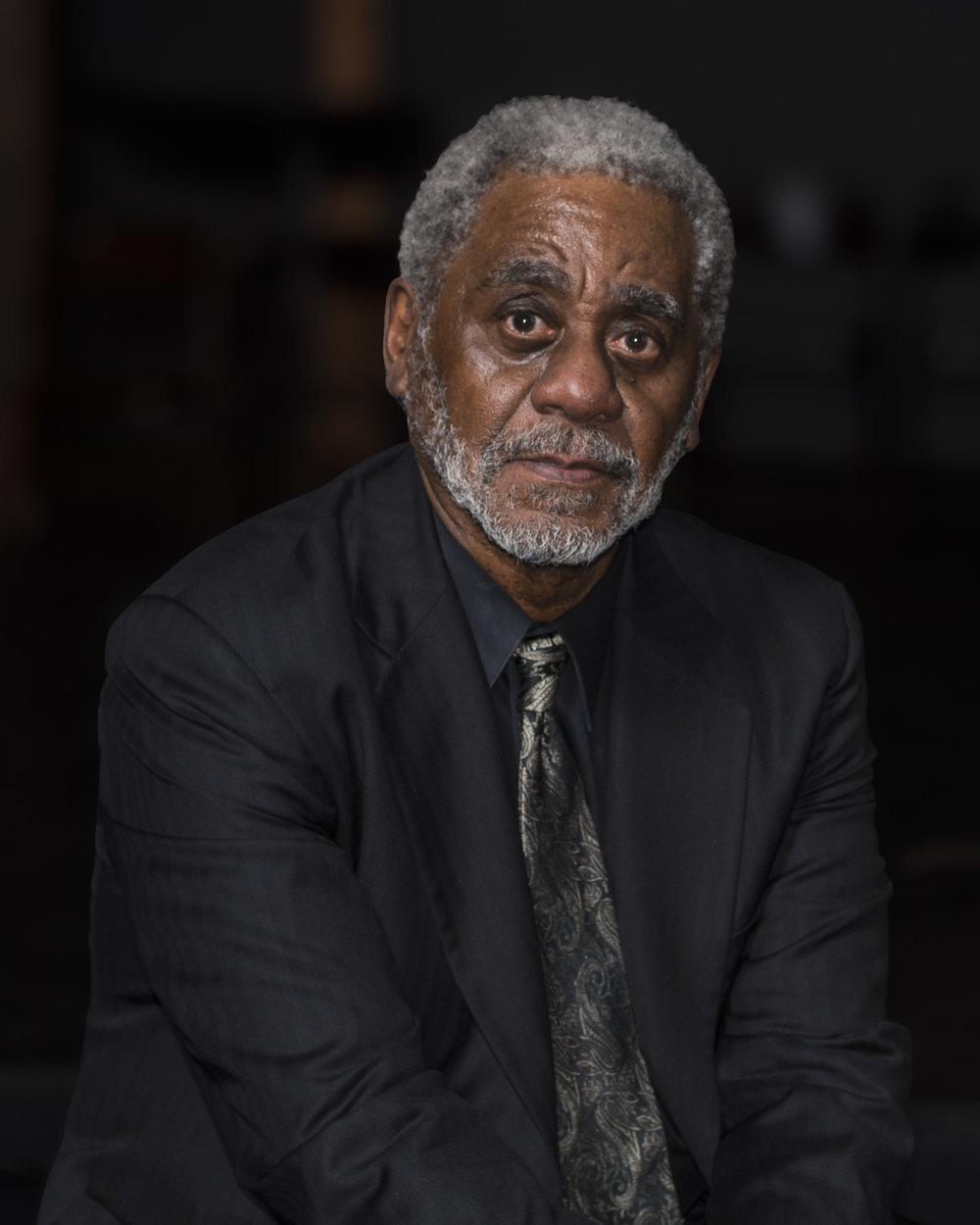

An Interview with Toni Ann Johnson

I first met Toni Ann Johnson in the early 1990s when we were both reading and writing poetry in Los Angeles, and we reconnected over Zoom during COVID. She remains as candid and honest as ever, sharing her opinions and experiences, and as always, underscoring how literary expression requires a fearless inquiry into our deepest past in order to create words that resonate in the present.

Johnson’s story collection explores the complexities of a family whose actions challenge ideas of race, class, and beauty in a small, white, affluent town. Any similarities to her own life are, well, intentional. Selected by Roxane Gay for the 2021 Flannery O’Connor Award, Light Skin Gone to Waste (UGA Press/October 2022) exists, as this interview reveals, in the space where memoir takes flight into fiction.

The collection joins Johnson’s dazzling writing credits, which include an award-winning novella Homegoing and novel Remedy for a Broken Angel; the screenplays Ruby Bridges, Crown Heights, The Courage to Love and Save the Last Dance; and the play Gramercy Park is Closed to the Public. Johnson is a literary provocateur not just in the usual genres but also has written two books on beauty, Vibrating Beauty and Vibrant and Clear. But then multiple platforms are part of Johnson’s career which began as an actress and singer. She later earned an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University Los Angeles, where she currently teaches fiction and screenwriting. She is a dynamic stage presence, so if you have the chance to catch a literary reading—go!

Dr. Stephanie Han

There are elements of this book that seem to resemble your childhood. Fiction is fiction, but there are emotional truths in a writer’s life that resonate and work their way into fiction. Can you speak to the idea of genre—fiction or non-fiction, autobiographical fiction and what choices you make because of your genre choice?

Toni Ann Johnson

This is autobiographical fiction. I had thought at first about doing memoir, but I wanted the freedom to invent and play and create what didn’t exist but what was based on what did exist. For example, the character “Emily” is based on my grandmother, but my real grandmother’s personality wasn’t that fun or interesting to write. So I created a broader, more annoying character and had fun with her and the way she played off the other characters.

I started working in memoir and then deliberately began inventing characteristics with my characters that were more interesting to me. I also wasn’t present for some events I wanted to write about, so I had to invent some elements. While I wanted to do a true story, I did not want to have to stay within the bounds of the actual facts. I had more freedom doing this as fiction, though all the stories were inspired by real events.

Stephanie

You are a screenwriter, and thus prioritize both structure and dialog. When writing fiction, do you work out the structure first? What is your process of prose vs. screenwriting?

Toni Ann

Great question. Yes, when I write screenplays I absolutely prioritize structure. It’s essential. In fiction I do have some idea of where a story is going. So I will beat out an approximation of a structure and try to write to the point that I’ve chosen for the end. However, in the execution of a work of fiction, you have to have room for surprises and so sometimes things shift depending on what discoveries come about. But I tend to know generally where things are going. I start with a character and what the character wants and/or needs and I go from there, which is similar to how I approach screenwriting, but I don’t always beat out a three-act structure for stories. With these stories, because they were all inspired by real events, I did have a good idea of how they ended, but sometimes the ending did change a bit.

Stephanie

You write expert dialog–how do you inhabit your characters? Tell me about your creative process.

Toni Ann

Yes! I play all the characters as I write them. I was an actor and that is the perspective I write from when I’m focused on character. I am them. I become all of them at some point. I feel their emotions and from their emotions I intuit what they will say.

Stephanie

Your book speaks to how we construct identity, across race, class, geography—what’s your take on how race is embedded in ideas of class structure, or vice versa? What do you think it means to claim a Black identity now as opposed to when you were growing up?

Toni Ann

I wrote about a time when most people thought all Black people were from a low socioeconomic class. My family was not poor, but teachers, sometimes other people in the town, and elsewhere would make these assumptions about what my family could do and what they thought we would do. I had a teacher call me a liar because I said I’d traveled to Japan.

As far as how I saw my Black identity back then, it changed. When I was under 13 I wanted to be white. I wanted to fit in where I was. When I decided to cut my hair off it was me saying, “This is who I am and I don’t give a shit if you don’t like me because I’m Black. I will not try to be like you anymore.”

Now, I don’t struggle with my identity. I reject the kind of essentializing I experienced in my 20s when Black people told me I wasn’t supposed to do this or that because I was Black or I couldn’t like certain music or dance the way I did because I seemed like a white girl. I am secure in the fact that I am Black.

I chose to live in South Los Angeles. I’ve been in a Black community for nearly 20 years. I bought a home here, pay taxes here, and invest in business here. My choice is political. I don’t care what white people think of that. Sometimes white people look at my partner (he’s Asian) and I as if we are crazy because we LIKE living here. I love my neighbors. I didn’t have an opportunity to live around Black people as a child.

I’ve also had the opportunity to test my DNA. I can see that I’m Nigerian (among other things), but I can make the connection to my specific African ancestry. I didn’t know those details when I was kid. And in my late teens I found out my mother was adopted and that she was biracial. It stunned me. I was confused about who I was. Her father was Jewish and I know her DNA is 50% Ashkenazi, so that was a significant difference in what I thought about who I was. But now, I’m Black. And White. I have a lot of European ancestry, but I identify as Black, not biracial, even though technically I am. Both parents identified as Black and culturally that’s what I am. Growing up in an all-white environment did challenge that identity. I felt like a fraudulent Black person for a number of years even though I really wanted to connect with Black culture. I don’t feel fraudulent now.

Stephanie

I always think that we are trying to answer some questions when we write a story or piece. What were your questions? Was the entire collection planned?

Toni Ann

It was always going to be a collection. I was in graduate school when I began writing the stories. I’d been inspired by the collection The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven by Sherman Alexie. I saw my collection similarly in that I would track some of the same characters over a period of time.

What I was trying to work out in the stories was an understanding of my parents and myself. I was gaslit for years. They [my parents] said it [my childhood] wasn’t that bad. They had no empathy for what I went through, and I was trying to understand why. What was at stake for them? Was it merely narcissism or was there more to it?

I think THEIR identities were more fragile than my own. I think my father craved acceptance by his professional white community and my mother craved to be valued and seen as a desirable partner. Part of that was being the pretty wife of a professional man and living well, traveling, and having nice things. The marriage falling apart was threatening to her identity. Her self-worth was a bit wrapped up in the image. Also, she’d been abandoned in childhood and I think that trauma was never addressed and then triggered by my father abandoning her.

I tried to see inside their weaknesses, to understand them and have some compassion for them while also validating my experience.

Stephanie

Did you get closure with your parents because of writing the book?

Toni Ann

I don’t speak to my mother as a result of working on the book and the way she reacted to my asking her about the incident when I was sexually abused in Africa. I would say yes, I have closure, however, it has not ended in an ideal way. I’m done. My mother has no empathy for the fact that I was sexually assaulted as an eight year old and I cannot continue a relationship with someone who can’t at least recognize that the incident was painful and caused me lifelong harm.

Stephanie

What were family and close friends’ or neighbors’ reactions to this collection?

Toni Ann

There was an earlier version of the book that had stories from my sister’s point-of-view and I was worried about that because I have no desire to cause her any discomfort. Those stories were removed from the book. As far as family, it’s very small, and most of my family doesn’t read my work. If they do, they don’t comment. My mother will probably read it and she might hate it. I don’t care. Neighbors are dead or the characters are composites for the most part. And I don’t think most of my neighbors from that time would read a work of literary fiction. Even if they started it, I don’t think they’d finish it. If they do, the ones who were racist back then will have the same attitudes now if Facebook is any indication of their attitudes. There is no one in particular whose opinion I’m concerned about.

Stephanie

Many writers, especially women writers I have taught, face fear when writing–of truth-telling, of writing something that might hurt someone or even writing what they themselves do not want to face. Thoughts?

Toni Ann

I was afraid of my mother and now I’m not. I wanted my mother to love me and she is not capable of that. She is a narcissist, and she’s gotten worse with age. The only fear I had has already happened. I have to face that my mother doesn’t love me. I have been writing about that since the first book Remedy for a Broken Angel. With that now accepted, what else is there? What could be scarier than not having your own mother’s love? So no. I am not afraid of telling my truth. I don’t feel I have anything to lose. And I gain me; I gain an acknowledgment of myself.

Stephanie

This is a question for young writers out there: Which story is the one that you feel that you grew from the most personally and/or in terms of your craft?

Toni Ann

“Wings Made of Rocks” is the story from Phil’s point-of-view, and it’s the story where he opens up to his mother about what she put him through. My father was dead when I began writing that story. I felt him while I was writing it; I felt his voice inside me. I felt his pain, his rage. His mother was a very complicated and difficult person and she, from what he told me, could never acknowledge his accomplishments. He was trying to prove his value to her. I think he gave up on some level, but I was with him when she died, and I could tell there was still some desire to connect with her. I wrote a story about it that was also cut from the book. He was late to her funeral. I think my father suffered greatly with the loss of his father and being raised by someone who was not demonstrably loving toward him. I gained a bit of empathy for my father. He did a lot of terrible and cruel things to our family, but he was in pain. Same with my mother. I have empathy for both of them.

Stephanie

Black women’s narratives often explore how skin tone affects judgments of beauty. You’re also an author of two beauty books Vibrating Youth and Vibrant and Clear. What’s your personal relationship to this challenge that women face?

Toni Ann

This is so complicated. As a kid I wanted to look like the women the dominant culture said were beautiful. I wanted to look like the pretty white girls I was growing up around. I mentioned before that I decided to cut my hair off. That was when I began to shift. My cousin, who was Black, had an influence on my shifting view of what beauty was. Yet even she told me not to cut my hair! But I did it to make a statement, to say that I am happy to be myself, kinky hair and all.

As I’ve gotten older my idea of beauty has moved away from being attractive to men to being the best version of myself I can be. It’s about health and being happy and vibrant and emotionally at ease. I think getting older has been the thing that’s made me happy with myself, even as I fight the signs of aging, I am more comfortable because I’m really not trying to be beautiful for anyone but myself. And I accept myself for the most part, imperfections and all.

Stephanie

I was lucky enough to see you in your play Grammercy Park is Closed to the Public. You’re a fantastic actress and singer, what prompted your pivot to writing?

Toni Ann

I started writing mostly to support my acting. Being so light during the 1980s people didn’t know what to do with me. I couldn’t play many Black roles because they didn’t see me as Black enough, whatever that means. I wrote in order to have roles to play. But I loved writing. I was able to do it as an art form without having to have permission from anyone. Writing developed mostly because it was something I could do. I took a class with Stella Adler in script interpretation and some of the things she taught about playwriting really appealed to me, and I got caught up in the idea of exploring social situations and the politics of a particular time while also exploring characters. That was probably my biggest attraction to moving into playwriting, which then led to screenwriting. I still love acting and I do it when I can via my books. My public readings are like little stage performances. I’m happy to be able to give myself those opportunities to act.

Stephanie

Do you have any advice you’d like to tell women about navigating life?

Toni Ann

I think as women we’re conditioned to nurture other people and to put everyone else’s needs before our own, which can lead to allowing people to violate our boundaries. I would say it’s okay to do that for your kids to some degree, but you don’t owe anyone else the right to overstep your boundaries. I allowed it from men, from family—for a long time, and I did it because I wanted to be loved or approved of. That never really worked. And in hindsight it wasn’t worth it. I would tell women value yourself as much as if not more than other people (children excluded). Don’t always put yourself last. It doesn’t yield what you hope it will.

Images courtesy of Toni Ann Johnson.

Dr. Stephanie Han is the author of the fiction collection Swimming in Hong Kong and teaches women’s creative writing workshops that focus on empowerment through narrative. She lives in Hawai‘i, home of her family since 1904.