Memoirs of an ‘Opihi

In a nimbus-white laboratory, a limpet materializes.

The anatomy of the room lacks corners, a continuous construct with minimal disruption of detail. In it are two scientists in uniforms as seamless in presentation as the room, without any discernible features except for their glossy, uninterrupted surface coverings that refract and reflect one another.

One of the scientists reaches out, plucks the limpet from the air with slender fingers, and marvels at the contrast of conflicting textures, patterns, colors, and forms. “And here, another smaller life form encased in rigid conical calcium carbonate. Basic triad of pleural, pedal, cerebral neural clusters. Typical lumen. Three-chambered circulatory. Ocean dweller with adhesive secretion and suction. They display the same phenomenon.”

The other scientist runs a needle-thin caliper leg along the ridges of the shell. “A thing of beauty. Such inward simplicity.”

“Which is perhaps why it’s such a strong conduit.”

“Same frequency?”

“Hard to say outside of these touch points…” the scientist says archly, “but yes…” and they both laugh. The scientist places a wand against the limpet’s shell. A face shield blossoms, calcifies, glows. “Not to bring the mood down. But this one in particular tells a sad story.”

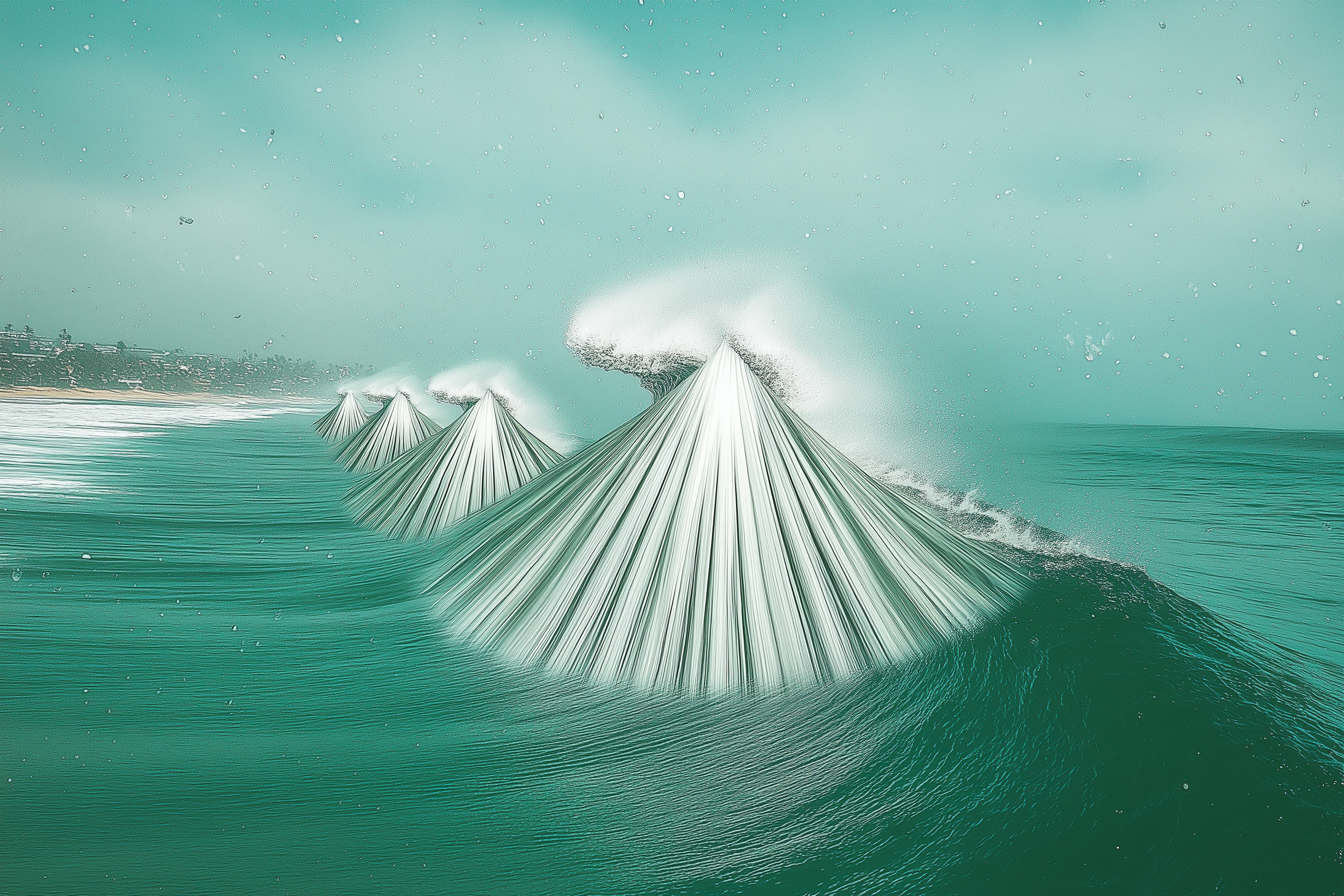

In the face shield, images are projected—not by light, but by a form of memory. They dance against the scientist’s retina. From the conical apex of the field of vision, the shell reveals a blueprint, lines from a vanishing point, they begin to waver and warp, overlapping each other as the ridges change direction, reforming a number of different topographic atolls, then the projection finally gives way to the creased and weathered blueprints of a woman’s face in the form of Evelyn.

She is an elderly woman living on the island, driving along the coast, and turning into a small neighborhood, eventually entering the driveway of a modest home. Another woman greets her, and they exchange gifts. The older woman takes out a small cardboard box filled with passion fruit and hands it to the homeowner. The owner then runs inside and brings out a foil tray of baked banana bread. They thank each other, make small talk, and then the older woman drives off.

Evelyn returns to her simple cottage, in the backyard of a larger home—a home that she owns, but rents out to a young family. She is content to live in the smaller unit and uses the family’s rent to supplement her small retirement income. The presence of others nearby also gives her a sense of peace.

In her kitchen, she cuts the banana bread and separates it into ziplock bags. Then she walks out of her home to her neighbors’ homes, visiting them one by one, handing out the ziplock bags of banana bread, leaving them on doorsteps, sometimes being invited inside, and other times being thanked but without any other reciprocal gesture.

Some days she volunteers at her church, helping with fundraisers, cooking batches for senior meal deliveries for those not much older than herself. She participates in beach clean-ups when she has the energy, wearing a wide sun hat and long-sleeved shirts to protect her arms and prevent a recurrence of a basal carcinoma that she had once had removed.

She returns home, and when the sun begins to set, she drives to the nearby beach, parks along a dirt road, walks down an uneven path, and sits at the shoreline to watch the sunset.

Many begin to question her motives. What did she want out of these exchanges?

“Oh, she has a knack for seeming to give favors when it’s actually more to her benefit.”

Around the island she went, delivering and accepting, volunteering with a theatrical magnanimity and inexhaustible generosity. And at the end of the day, she would retreat to the shore, walk along the criss-crossing berms woven between the deep tire ruts along the rocky dirt road to the beach with the blackened sand, and watch the setting sun illuminate a plank of fractals making and remaking themselves toward the horizon.

Her eyes would say hello and goodbye at once.

The limpet shell dazzles the scientists, as parts of it shimmer the way the black sand did when Evelyn sat along the shoreline.

Up close, they can see the jagged edges, the way the ridges of calcium carbonate fold down and up, endless waves moving in a circular pattern forming rugged miniature trenches, a spider web blueprint filled in and corrugated, cusped edges reaching out from the center toward the void, the way Evelyn's fingernails did from her outstretched hand.

At the apex, the material turns white, like a snowcapped mountain. Traces of it drained out through grooves, white lines leaking through phases of midnight and obsidian, burnt wood, and sepia. From above, it resembles a parched island, and the scientists watched miniature clouds floating over its surface.

“These things tend to hallucinate,” one of them said.

One day, she visited the grocery store in need of red beans for a sekihan she had planned to make and deliver to her co-volunteers at the nearby food bank, when she saw a fellow church member known for gossipy nature.

She turned and walked in the opposite direction, and considered leaving the store and waiting in her car until she saw her leave. She meandered down the bread aisle and rounded another corner, inadvertently coming face to face with her.

“Oh, Evelyn! How are you?” the woman said, brows knit with concern. “We haven’t spoken in a while.”

“Hi Lynne… No I was planning on baking some ____ for the church workers. I’m not sure if I’ll be helping with the food prep this year.” She clutched her purse protectively to her sternum. Every part of her withdrew.

“Oh, I know how you feel. I don’t let those people bother me.”

There it was. A colorful trap lay out within a few minutes of encountering her, visible, bright, and gleaming, calling for attention.

“Well, no, of course not… But… Why would they bother you?”

“Oh, you know, they gossip and chatter. Sometimes it bothers me what they say about you. It’s so unfair.”

Evelyn recoiled. “Oh, I see. Well, I won’t be seeing them this year, so I don’t need to worry…”

“Yes! Don’t worry about it! They love you! You’re practically family.”

“Sure, family.”

Evelyn could see that she wanted to continue on the matter, but she excused herself and left the store without her groceries.

“You give too much,” her late husband, Toma, had said decades ago when they were still young, and finding their way through the community. “It makes people awkward, like they need to give something in return.”

“I don’t expect anything! I just wanted to do something nice!”

“You don’t need to give them overly generous gifts. A nice smile, hello, warm hug will do.”

“I just want them to be happy. How do you gauge how much to give?”

“If it feels like too much, it probably is.”

“But it never feels like too much.”

"This isn’t a popularity contest.

“You’re the popular one.”

Toma was very popular, and the household was like an eventful tide pool, where the tides and currents brought about guests from all walks of life. Visitors from around the world would drift in and out. As a fisherman, he would offer large meals with the day’s catch. He would take visitors out on his boat and entertain them with stories about the island, culture, and his family. People loved Toma.

Evelyn would sit shyly at his side as those nights would become more and more boisterous, with guests scattered throughout the living room in a random assortment of chairs, beanbags, and futons. Toma, tearing the caps off with his teeth, the room lit only by a red lamp, and Christmas lights, a wobbly RCA warbling out Alfred Apaka or Arthur Lyman, recounting the last time he had speared a Tako only to have it taken by a tiger shark. The more energized he got, the more depleted she felt.

But she studied him, his curiosity with people, his fearless way with holding the room enthralled with a story, while also knowing how to get lost in the stories of others, no matter how unreliable their narrator.

“Don’t mind my wife, she’s just the quiet type. So shy!”

For her, his generosity was in his being, his outward persona. What did she have if not items to give?

At first, there was the geosphere—the ever-shifting surface of the earth’s landmasses and bodies of water, canyons and mountain ranges, atolls, islands, and continents. The biosphere would follow as life forms populated every surface and hollow. The sphere of human thought would soon come to encompass both spheres.

“Very mysterious, indeed.” The scientist said of the limpet, “These wavelengths accrue around unexpected objects, none of them the wiser. This little thing knows no more of its own transmissions than a mirror of what it reflects.”

"Desolate. We're touring the ruins of consciousness through a peephole."

"Now, just residue."

"Well, it participates in the same cyclical rhythm. It finds a flattened and slightly recessed bed in the rocks it adheres to. Grazes in the periphery and then returns to its bed where it secures itself. I don't understand the connection."

A red pickup blasts into the dirt path in front of the house. The driver sounds the horn impatiently. Toma steps out, and Evelyn follows. He leans against the driver's side door. Evelyn can barely make out what they are saying. There are three others in the bed of the truck. Another fishing outing, she assumes.

“‘Opihi,” says Toma, rushing past her back into the house for a butter knife and a cloth bag. “For tonight’s pūpū.”

‘Opihi picking, she had once sat by and watched from afar as he ran along the rocks on a sloping intertidal zone, climbing down and then scrambling up as the waves crashed just a few feet below him. She had watched the way he ran and jumped from one rock to another, almost without looking, almost as if every blind leap had a forgone conclusion, his foot, landing firmly on one porous lava rock, then leaving the earth again as he jumped to another burnished, porous stone on the rocky cliff, while beneath him, in the crevices and chasms between the large black boulders the white water churned, sometimes erupting out of blowholes.

“Bum-bye then!” he called out and jumped into the bed of the truck where a few of his friends were sitting. The truck lurched then skidded, jostling the laughing crew in the back, a cooler sliding against the corrugated aluminum flooring as the truck spun out into the road.

It was the last time she would see him. While he was scouring the cliffside, a rogue wave lurched up and slammed into the wall, then receded so quickly the force of it dragged Toma’s body along the reef, and into the depths. They would not recover his body until a week later, snagged under a reef shelf.

For Toma, this was a moment of simplicity. The effects of two beers swimming loosely within his system, his limbs felt limber and ready for anything. The ‘opihi, just a foot out of reach, was the perfect size—a yellowfoot, the most prized of all. Beyond it, another small cluster, a village of huts grouped together. The ocean surged and bellowed into the hollows and crevices.

His butterknife caught a glint of sunlight. The limpet, with its primitive eyelets, sensed the change in light and clamped down along the smooth algae-coated surface.

Toma edged the blade into the exposed slits between the limpet's shell and uneven stone and worked its way under. For one moment, his entire world was the hard shell, the cool stone, the white sun glinting off the metallic blade, and then a sudden wave.

Years went by, all of them spent alone. She had inherited the home and kept it clean. She sold the boat to one of his closest friends, who insisted on giving her a generous price for it.

She stayed away from the ocean. She watched the husbands of her friends grow old, while in his own place, a youthful outline of Toma graced her periphery.

An earthquake off the coast of Peru measured at 8.4 on the Richter scale. The resulting Tsunami traveled 7,000 miles before hitting the first shoreline in a sequence of islands one summer evening under a hunter's moon.

The seas receded as if the horizon was drawing in a deep breath, revealing the broken objects long-submerged at the bottom of the ocean. Hotel lawn chairs, sunken vessels, debris from hurricanes past.

On this day, after helping a small group at a tea ceremony, Evelyn drove to the shoreline. The emergency siren had been blaring, but it was not the first of the month, when tests were conducted.

Evelyn sat on the shoreline, as she normally did at this time of day, and watched the water reveal its sunken treasures.

From afar, she saw a man walking among the exposed reef, stone, and junk, pausing to examine one bauble after another. He straightened and waved.

“There he is,” she thought to herself. “My Toma.”

The rush of the water was swift, a surging wall of frothing and churning foam followed by a thunderous crackling that enveloped her fragile frame.

“Did that really happen?” asked the scientist, shutting off the face shield.

“Unlikely. These things are all such unreliable narrators. Especially at this level. It churns experience into these odd projections.”

The limpet vanishes.

“So what became of that woman?”

“Those archives are long gone. But I suspect she lived a long, eventful life on her own terms. As all did in those days.”

“Are they all like this?”

“So far.”

"All of that in this little lifeform. So how do we classify this one?”

“Just another dream of a thing long gone.”

Images by James Nakamura and Midjourney.

James Nakamura is the creative director of HONOLULU Magazine. You can read his essay about AI, If You Can Imagine It, It's Ours, and a report, The Disappearance of Beach Glass in Hanapēpē at The Hawaiʻi Review of Books.