I’m Having My Baby!

The trope about being a single mom is that it happens to you.

Your partner leaves. Your partner dies. Or, having the baby was unintended in the first place.

Whatever the case, more and more women are choosing to have children on their own and putting in a lot of effort into it—including author Virginia Loo, whose How to B, published this month from Saddle Road Press, is one account of making this happen.

How to B unravels the plot of why and how someone might choose the solo path to pregnancy and parenthood. It turns out getting pregnant as a single woman is a wild adventure for Virginia Loo, but perhaps not the hardest part. Requiring more nerve is confronting expectations about working women in the world, navigating the values of her own family, and maybe mostly reconciling with herself.

—Susan Essoyan

An Interview with Susan Essoyan and Virginia Loo

SUSAN ESSOYAN

This is an apt time to be publishing your book given that women’s reproductive rights are under attack and the issue is so much in the news. You first started writing it 10 years ago. Can you tell us about your original intentions and how the book evolved?

VIRGINIA LOO

I started writing sections when my son was just 1 or 2, and I was just coming out of that very intense period of figuring things out and starting to feel that this was going to be OK. It was, originally, these funny anecdotes about doing IVF and just trying to find a donor. I wanted to capture how strange and bizarre the whole experience was, so it really started off more at that level and tone.

And then I put it down for a bit. Things got a little busy and maybe five or six years later I picked it up again. And then I was thinking, well, if I wanted to make it a fuller piece, now I could go into aspects of that first couple of years of figuring out being a single mom—that was its own kind of crazy. But then I put it down again. Working in these spurts of time, being at a different phase of how I thought about the whole thing changed the shape of the book a lot.

Reflecting on my own relationship with my mother started to be a much bigger theme. I hadn’t intended this book to get into that, but it just kind of came out. It was only maybe in the last two or three years where I was thinking I should really try to finish it. It’s been 10 years. My son is getting older. I needed to just finish it. [Laughs.]

SUSAN

That’s one of the things I love about it, the layering of your own personal story, how you fit in your family, how you fit in the world, how you fit solo parenting with your career, and the support that’s needed when you make a choice like you made. I think it will appeal to readers on lots of different levels.

This is a very personal and revealing story. And yet you strike me as a pretty private person. So did it start just as capturing the story for yourself and your friends? And how did you decide to kind of “bare all” in this way?

VIRGINIA

That’s a good question. I’m a little surprised myself how much I put out there. When I ask myself, “Why am I writing this?” there was a certain aspect, I think, of trying to capture my life before I had my kid. The people in my life never really understood what I did as a public health person. It was a very compartmentalized kind of living. I would go off and do work and then come back and have a completely different social experience because I wasn’t working with the people that I was home with, and they had no idea what that life is like.

So part of it was to capture that, put it all together to make sense on the page. And also for my son to kind of get a glimpse of what things used to be like. And maybe for myself to remember, because now my life is very different. Sometimes it feels very far away.

SUSAN

Did you intend to publish it originally?

VIRGINIA

I’ve dabbled in writing for a long time. And maybe in the back of my mind, I had this idea that I would love to publish something, but I don’t think I ever imagined that it would be a memoir-type project. I thought it might be fiction. But at some point, it felt like people who are being intentionally single moms is a bigger and bigger phenomenon. So the things that I went through to make it happen, dealing with the world, my own reconciling of the choices that I made and how I’m living—it might be good to share. Late in the process I realized this might be a really good thing to put out.

SUSAN

Your narrative flows easily and really pulls the reader along. And there are all these vivid, eye-opening anecdotes that make you laugh. Was it tough to write, or did you just kind of go for it?

VIRGINIA

A lot of it came pretty easily. The book moves back and forth in time and place, so it’s not a traditional narrative style. I think that it was very freeing because that’s kind of how I processed a lot of things. I’ve always felt my life has been a lot of different streams happening and then coming together in sometimes unexpected ways. And so being able to write like that and pull in, you know, things from deep memory, from my childhood, books and movies that have stuck with me, but also, like, what I was going through right at that moment was very freeing. And so that felt a very natural way to write.

In a memoir project, you have a little more of that liberty. I was telling my story so I could use a voice that felt very natural to me.

SUSAN

It’s really delightful but deep at the same time. When you dedicate the book to your son, you write “For B (but not until you are 18 or older)”. Is that realistic, given that it’s in the public domain? Won’t he have to deal with it sooner rather than later? How did you weigh the possible impact on him of its publication?

VIRGINIA

I do think about it a lot. I happen to have a fairly compliant, rule-following son, so I have a little bit of faith and hope. We’ve talked about it and I tried to explain to him why I think it wouldn’t be good to read it now. And maybe he doesn’t fully understand what I was trying to say, but I think he does understand that it would be better to wait.

It’s a pretty personal book; it goes into maybe some adult topics. But I think that’s not the main reason I wouldn’t want him to read it now. What I think about is there’s a lot of complex feelings you have when you are thinking about having kids and then when you are a newer parent. And so sometimes it feels tough. And I wouldn’t want him to walk away with the idea that this was ever something I thought was a bad idea or, you know, that there’s regret. As a younger person, he might not have the experience or perspective and could misinterpret something that has been a really wonderful but complicated thing.

“Coit Tower is on the cliff just above, and I find it comforting to have such a large hopeful penis symbol to my right. On my left is the lonely but lovely isle of Alcatraz, representing my uterus, surrounded by shark infested waters which symbolize my lack of sex life.”

SUSAN

Your relationship with your parents and your mom in particular is a crucial and often hilarious part of the story. In the book you describe their reactions to your sort of audacious plan to have a baby on your own. What was their reaction to the audacity of you publishing a book about it?

VIRGINIA

They’ve always known that I wanted to write in some way. And so they would be supportive of any project. They’d say, just get something out there. I didn’t realize it either but they probably didn’t know how much I would talk about our relationship and their perspective on this whole process. But they have both read it. And I don’t think they have reservations about it.

I write in the back of the book that I try not to identify most people in a way that they would feel uncomfortable. But my family, of course, didn’t really have a choice in that. They’ve shared it with their friends and it’s fine in the family. I think they have a sense of humor about it.

SUSAN

When you decided to have a baby, you wrestled with the idea of who should be your sperm donor. And at first you preferred an anonymous donor, until you started exploring the risks. Have you watched the recent Netflix docuseries about “The Man with 1,000 Kids”?

VIRGINIA

I’ve heard of it, but I have not seen it. But yes, exactly! Certainly I’ve read other stories of similar kinds of complications that come about now that it is so common to use a sperm donor to have a child. And what are the ethics? This kind of process always, I think, is far ahead of the ethical considerations of what might happen. And so it’s not surprising probably, that now people are really like, you know, did I walk into something that I didn’t anticipate, and now there’s some big consequences for my family or my kids to think about?

I found that there were so many questions to ask myself about how and why I did things in trying to have a kid on my own. Questions that maybe people having a child in a more conventional partnership don’t think too much about. Because it feels hard and there are a lot of hurdles along the way, the questions keep popping up. It starts with, What’s a legitimate desire to have a family or have children and who is a qualified person? And, How is that judgment baked into a health care system or what’s covered by insurance? I think those are interesting questions that sort of came out in this book. I didn’t intend to really examine it, but it came out when I was writing.

SUSAN

Ultimately, given the unknowns with anonymous donors, you settled on someone you knew. You made it clear that you wanted a donor, not a co-parent. But early on in the book, you noted that a child might want to know their father. How did that work out in your case?

VIRGINIA

My donor ended up being a very present person in my son’s life. And so that did evolve. That was not the intention going into it. It’s a really important part of the decision to have a child—knowing that a lot of different things can happen. Being able to do this with a person where I had that very strong relationship, to be able to evolve and talk about it, ended up being really important. I kind of had that instinct when I was thinking about it. So I’m really glad that I went down this particular path. Having kids is a chaotic thing, it makes a difference to have that preexisting relationship with the donor, to be able to work it out.

“The stakes involved in choosing a sperm donor from a sperm bank are higher. It’s not the same as finding a yard guy or a contractor or an electrician. Your yard guy could kill your favorite hibiscus, or your contractor could do a bad tile job. Those things can be fixed.”

SUSAN

The decision to solo parent in this way can be controversial. How are you handling that?

VIRGINIA

It’s funny the process of hearing what people think of the book is bringing up all the same feelings as when I was telling people that I was planning to have this baby on my own. I find myself approaching every encounter with a little trepidation.

The book feels so personal that when someone shares whether they like the book or not, it feels like they are also commenting on whether they agree with how I decided to parent. I always feel myself bracing a little bit, especially with the people that I know and that I'm close to, because hearing what they really think might hurt or not feel good.

SUSAN

What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

VIRGINIA

Maybe it comes back to the title. It had a very different kind of title early on in the project. I settled on this title because it struck me that a lot of what was causing me angst and uncertainty in that period of having my son is the expectations that we put on ourselves about how to be a parent, what kind of parent to be, what are the right circumstances and the right reasons to be doing this. And also growing up and having a lot of opportunity—[there are] these expectations of what you do with all that investment and the resources that your family’s put in you.

The time that I really relaxed and became comfortable was in shedding all the expectations of “how to be.” And so maybe that’s the cheesy underlying message. Just being OK, being yourself, however that is exactly, it’s going to be fine.

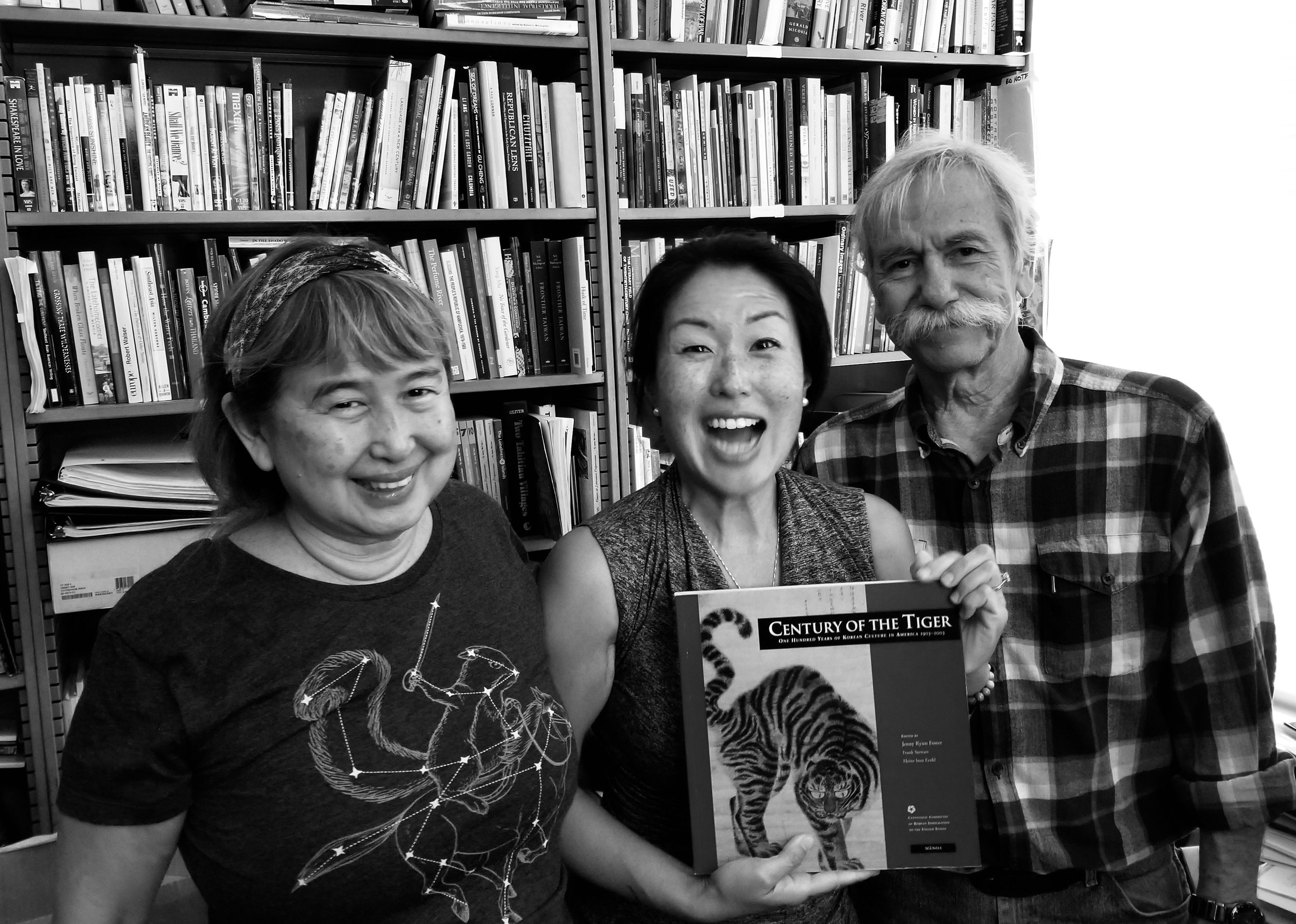

Susan Essoyan spent her career reporting for the Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times and her hometown newspapers, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and Honolulu Star-Advertiser. She specialized in education and social issues. Now retired, she lives with her husband in Pauoa Valley, where they raised their children.

Raised in Central O‘ahu, and living in (Honolulu) town for the last dozen years, Virginia Loo is a writer of short stories, long percolating novels, sometimes published poetry, and now a memoir about having a child as a single person. As an epidemiologist back in the day when nobody tried to estimate the chances of getting a respiratory illness from the person sitting next to them at a restaurant, Virginia worked for more than 20 years in HIV prevention in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Banner image courtesy of Aditya Romansa.